Nikil Saval and Pankaj Mishra on “the painful sum of things”

NS: Now that he has died, the preparation feels insufficient: the uneasiness remains. I suspect you feel it as well: how to speak about a writer whose work has been meaningful—–in my case, profoundly so; I could not imagine my life without it—–as well as a source of frustration or real pain. I have admired Naipaul as much as I have found him difficult to admire, a murky admixture that I find difficult to explain or clarify, and which I find with no other writer, to anything like the same degree. (Edward Said referred to his “pained admiration,” and dissonant phrases of that kind are scattered through appreciations of his work.)

PM: For many aspiring writers from modest backgrounds, in the West as well as in Asia, Africa, and the Caribbean, he was the first writer who made us think that we, too, had something to say, and that we, too, had an intellectual claim upon the world… In societies and cultures where the idea of a whole life devoted to writing and thinking is confined to the privileged members of the population, Naipaul’s example—that of a man making himself a writer through sheer effort—was a great boost.

NS: It is the nature of the societies we live in never to let you forget your luck, to point to any success as a sign of its ultimate justice; to make your rage against them seem like ingratitude. In the end, to an extent that I find debilitating, Naipaul was grateful. I know that the sense of personal injury, of grievance, that I feel in recalling these fundamental aspects of his life and art are disabling, feelings that one day might be transmuted into something different; a necessary distance. But I have yet to manage it.

September 19-28, 2018 in Donald Trump’s America

Milkman, by Anna Burns

Winner of this year’s Man Booker Prize for fiction. Opening paragraph:

The day Somebody McSomebody put a gun to my breast and called me a cat and threatened to shoot me was the same day the milkman died. He had been shot by one of the state hit squads and I did not care about the shooting of this man. Others did care though, and some were those who, in the parlance, ‘knew me to see but not to speak to’ and I was being talked about because there was a rumour started by them, or more likely by first brother-in-law, that I had been having an affair with this milkman and that I was 18 and that he was 41… It had been my fault too, it seemed, this affair with the milkman. But I had not been having an affair witht he milkman. I did not like the milkman and had been frightened and confused by his pursuing and attempting an affair with me.

Social media and the Rohingya crisis

Facebook commissioned an independent assessment of the human rights impact of the social network in Myanmar . It finds that it “has become a useful platform for those seeking to incite violence and cause offline harm.”

On the topic of the Rohingya refugee crisis, a book I’ve been in the middle of for a couple of months now is Myanmar’s Enemy Within: Buddhist Violence and the Making of a Muslim ‘Other’ by Francis Wade. It is a little bit dated since it was published in December 2017, but Wade seems to be the best Anglosphere reporter on the topic and relatedly the most compassionate. I recommend his July LRB article “Fleas We Greatly Loathe” whenever I can.

Bill Gates, unimpressed by effective altruism’s focus on existential risk

Ezra Klein: 99.99 percent of all the humans who’ll ever live have yet to be born. If that’s true, then even very small reductions in the danger of those future lives not happening begins to outweigh large improvements in the value of life now.

Bill Gates: Well, if you said there was a philanthropist 500 years ago that said, “I’m not gonna feed the poor, I’m gonna worry about existential risk”, I doubt their prediction would have made any difference in terms of what came later. You’ve got to have a certain modesty.

…If somebody thinks there’s a magic thing they can do today that helps all those future lives, in a free economy, they have a chance to build whatever it is they think does that. We do have a few things like climate change where you want to invest today to involve problems tomorrow. I’m always a little surprised there’s not more engagement on that issue. Pandemic risk, weapons of mass destruction.

But… there’s not many that we really understand with clarity, and so somebody who says, ‘Okay, let’s just let a million people die of malaria because I’m building this temple that will help people a million years from now’, I wonder what the heck they’re building that temple out of.

EK: A lot of people have become very focused on the question of AI risk. I’m curious how you weight that as a risk to future human life?

BG: And so they think that’s more important than kids dying of malaria?

EK: …I don’t want to put words in other people’s mouths, but as I understand it, the idea is there are a lot of good people working on malaria, and AI is so dangerous that it’s better for people on the margin to be working on AI risk now than to be—

BG: But most of those people aren’t working on AI risk. They’re actually accelerating progress in AI… They like working on AI. Working on AI is fun. If they think what they’re doing is reducing the risk of AI, I haven’t seen that proof of that.

Purity, by Jonathan Frenzen (h/t Eszter)

The inaugural selection for our unofficial grad-student book club here at Nuffield College. I didn’t like it and not knowing Franzen outside of this work, I found myself distrusting him with the subject matter. I couldn’t help thinking of this tweet from the @GuyInYourMFA novelty account:

story idea: a married man is so complicated and interesting that he sleeps with a 22 year old

— AUTHOR In Your MFA (@GuyInYourMFA) October 21, 2017

I’m not prudish about what I read, but I didn’t feel nearly enough reward for indulging 560+ pages of exhausting characters. I can appreciate the choice to use a cast of unlikeable in a novel called Purity, but the unlikeability of the author seeps through too much to justify the length.

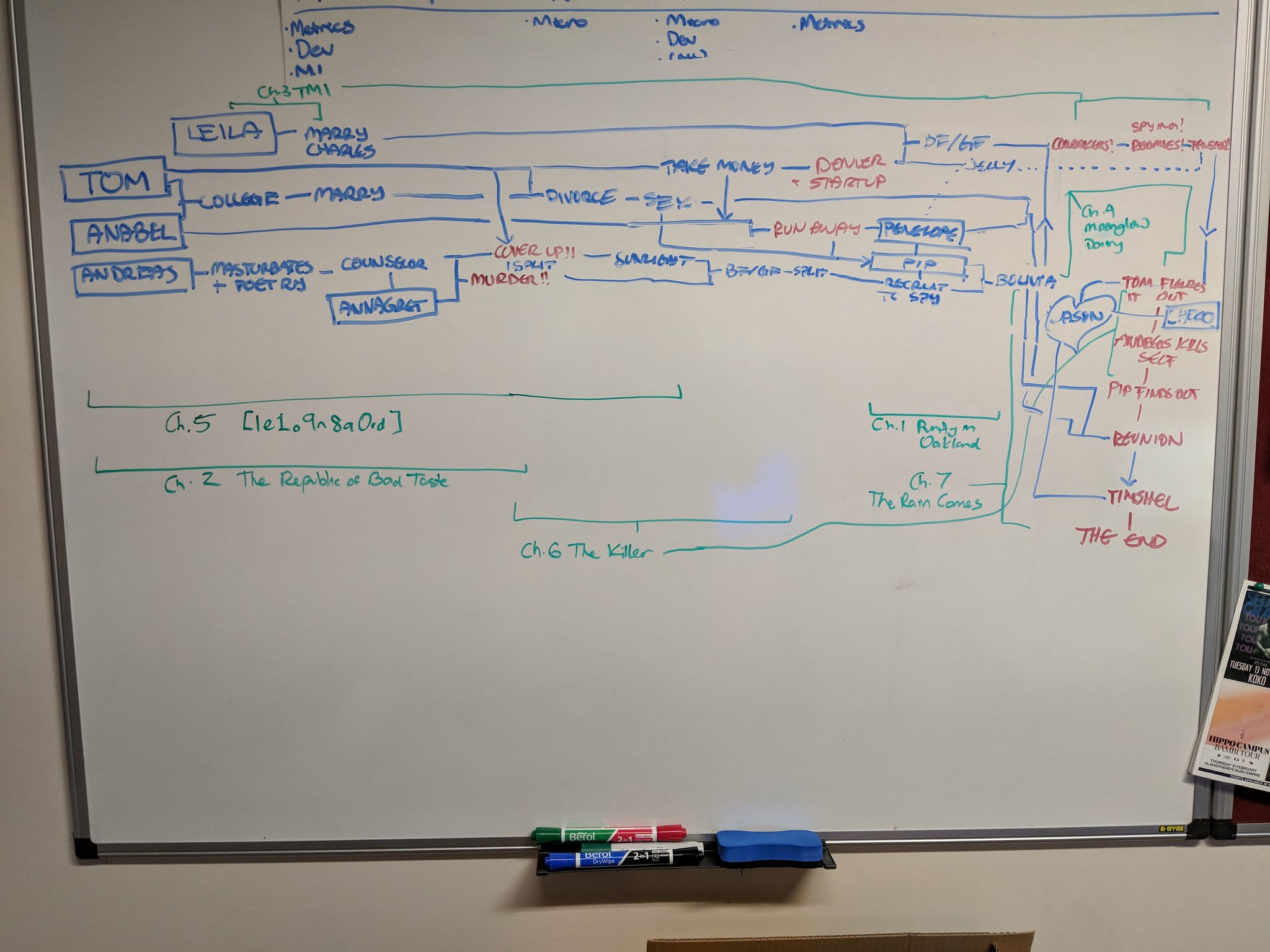

Spoiler alert, I also made this chart trying to chronologize the sequence of events in this novel, which jumps abruptly between chapters across space, time, and character perspective: