The Uninhabitable Earth: Life After Warming, by David Wallace-Wells

I’m not sure the title claim is advanced in the book or supported by the climate literature so some people may justifiably feel deceived (and maybe also by the cover; when the mass bee deaths feature, its connection to climate is dismissed). As far as I understand, certain parts of the world—small island nations and some vulnerable coastal cities—are on track to be submerged pending political intervention and others in South Asia and the Middle East will regularly have weather exceeding the limits of human survivability. But that’s just 30% of the world’s population for 20 days a year currently and maybe 48-74% of the population by 2100 depending on what we do. By then, that study estimates, many equatorial locations like Jakarta, Indonesia are expected to experience deadly heat 365 days a year . Luckily, the city will probably be completely below sea level anyway. So literally the entire Earth uninhabitable? Doesn’t seem likely. ‘Just’ conducive to heat death on a daily basis for hundreds of millions thousands of miles away from political influence and the land inhabited by 5% of the world’s population will experience chronic submergence. And then the next century will start.

To be less flippant, the title serves mostly to make explicit the book’s origin as the author’s 2017 long-form (here ’s a version annotated by scientists), which quickly became New York magazine’s most read article ever (though it’s since been unseated by a “Fire and Fury” excerpt). Many called the original article’s focus on and presentation of worst-case scenarios sensationalist, maybe most prominent among them the climatologist and climate science communicator Prof. Michael Mann. In Mann’s words , his problem with the article was “the fact that there were SCIENTIFIC INACCURACIES that PREFERENTIALLY fed a somewhat doomist narrative.” In contrast, with this book adaptation, “David has done his due diligence, vetted the science, and gotten it right.” Since the publication of the original article, Mann and Wallace-Wells have participated in a public conversation hosted by NYU to discuss the communication of climate science and have jointly promoted the book .

To me, the book is overwhelmingly a success and potentially an important leap forward in advancing how the public understands the enormity of the climate change problem. By ‘public’, I also mean to include academics from other disciplines and the op-ed intelligentsia who’ve decided to stake a claim of expertise in the area now that the Green New Deal proposal has made the topic politically relevant.

Part of this contribution may be its updating the language of climate change. “97% consensus” and the questions of its happening and of human attribution are old . Here’s some new:

- 250,000 additional deaths attributable to climate change every year, conservatively

- 200,000,000 as a median estimate for the number of (mostly intranational) migrants seeking refuge from climate by 2050. I’m being intentionally wordy because a “climate refugee” isn’t officially a thing yet . 70% of these will be from sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, and South Asia.

- Climate change as “genocide,” as the foreign minister of the Marshall Islands put it

- The “catastrophic convergence” , the term introduced by journalist Christian Parenti in 2011 to describe the intersection of imperialism, neoliberalism, and climate change

- Environmental justice as a “climate caste system” , a Wallace-Wells coinage

- Climate reparations

The main criticism I’ve seen levied against the book and similar ones has been that they are alarmist. While sometimes an appropriate epithet used to throw cold water on inappropriately extreme messaging (see the cloud study mentioned at the bottom of this post), it’s also had the effect of dismissing necessary attempts to bring the public up to speed with our current understanding of the consequences of climate change, which has advanced significantly in recent years. Wallace-Wells’ work embraces the adjective: his recent NYT opinion piece adapted from the book uses the headline “Time to Panic.” The book’s first sentence, the same as the original article’s, is “It is worse, much worse, than you think.” And on page 138: “If you have made it this far, you are a brave reader.”

This gets to the heart of an outstanding issue with public engagement on the impacts of climate change. Any honest reading of the growing interdisciplinary literature on climate impacts should induce panic, a natural expression of empathy for the most vulnerable human beings on our planet. From my perspective, to admonish those who feel fear amounts to promotion of injustice and ignorance. Two climate journalists discuss that here .

Noah Smith recently had what I think is a lazy take on the dangers of climate panic when comparing being upset by the prospects of climate impacts to the fear to itself be feared during the Great Depression:

I think there's something to this. FDR didn't sell the New Deal by screaming about the dangers of total economic collapse. Climate change IS very scary, but we can't afford to panic, because when we panic we tend to do silly, counterproductive things. https://t.co/GUybhptrha

— Noah Smith 🐇🇺🇸🇺🇦 (@Noahpinion) February 26, 2019

To hone in on the Great Depression analogy, there is no meaningful parallel between the mass panic of bank runs collapsing the international economy to the supposed chaos that would ensue from learning what climate change does. When has high public concern ever led to commensurate or over-compensating policy ? As pointed out here , the metaphorical mapping would not have the concerned public playing the FDR role; it would be more like everyone but FDR noticing the stock market crashing and then pressuring the bumbling President to take action at an appropriately revolutionary scale. If made in good faith, it’s asilly if not harmful argument for Noah to half-ass for an important topic.

It also seems to be the opposite criticism to the typical one made about alarmism, which is that it induces political defeatism and paralysis. I realize I’m focusing on a single tweet, but Smith has over 135,000 Twitter followers and a Bloomberg column so his thinking out loud in 280 characters at a time to try to reconcile his staunch neoliberalism with the catastrophic embodiment of its shortcomings is unfortunately influential. A bit more on this later below.

We’ve lived with climate indifference for the past few decades and it hasn’t produced any meaningful policy. In contrast, the urgency of the young Democratic progressives made climate change maybe the defining issue of the 2020 Democratic primary before they were even sworn into Congress, this after none of the US presidential or vice-presidential debates from the last two races included a single question about climate change . To drive home the opportunities climate indifference has squandered, consider this hypothetical that Wallace-Wells presents:

“If we had started global decarbonization in 2000, when Al Gore narrowly lost election to the American presidency, we would have had to cut emissions by only about 3 percent per year to stay safely under two degrees of warming. If we start today, when global emissions are still growing, the necessary rate is 10 percent. If we delay another decade, it will require us to cut emissions by 30 percent each year.”

The idea of fear inhibiting meaningful action is disputed in social movement theory and I hope I am not out of line in invoking civil rights movements :

I want you to understand how overwhelming, how insurmountable it must have felt [in the Jim Crow South]. I want you to understand that there was no end in sight. It felt futile for them too. Then, as now, there were calls to slow down. To settle for incremental remedies for an untenable situation. They, too, trembled for every baby born into that world.

You don’t fight something like that because you think you will win. You fight it because you have to. Because surrendering dooms so much more than yourself, but everything that comes after you. Acquiescence, in this case, is what James Baldwin called ’the sickness unto death.’

What, now, do you have to lose? What else can you be but brave?

In 2017, 150 Indians carried the skulls of their fellow farmers —some small subset of the 320,000 driven to suicide due to uncharacteristic climate-driven crop damage between 1995 and 2016—and trekked to the capital Delhi to protest naked and sitting down for almost a month to demand a policy response: “We wanted to symbolically shame our leaders into action.” So the notion that the relatively wealthy and climate-insulated can’t be trusted to inform themselves about climate change because they might accidentally do too much out of fear is offensive, in my opinion. Maybe anti-alarmism is also part of the new climate denialism .

It is this notion of injustice that I think resonated most while reading this book and even while contributing the little I have to climate research. Wallace-Wells make the point that we’ve now expelled more greenhouse gases while aware of its contribution to the global greenhouse effect than we ever did in ignorance going back to the dawn of the industrial revolution. There is an intuitive unfairness now in “trying to bring many hundreds of millions more into the global middle class while knowing that the easy paths taken by the nations that industrialized in the nineteenth and even twentieth centuries are now paths to climate chaos.”

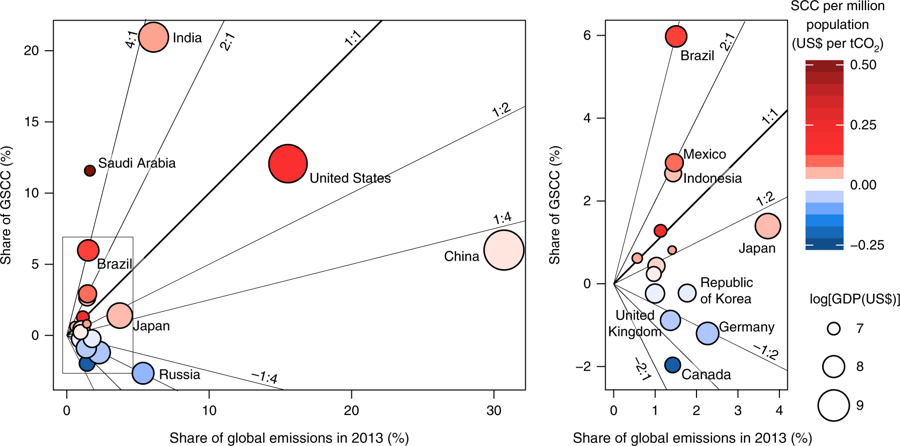

The legacy of colonialism, slavery, and Western exceptionalism permeate the narrative of climate change. The figure above shows that Saudi Arabia, India, Brazil, and Indonesia are expected to bear the largest share of economic growth impacts relative to their contribution of carbon emissions. For India and Brazil, this ratio is estimated to be roughly 4:1 (but maybe President Bolsonaro’s deforestation can swing the ratio towards equity ). The two biggest emitters—the United States and China—are net beneficiaries by this definition, China by a less than 1:4 ratio.

There is a normalized disregard for the well-being of those in

vulnerable

areas

already suffering tremendously from climate change even among those

prepared to embrace the science of climate. How else to interpet the

Nobel committee approving the Nordhaus recommendation that 3.5 degrees

of warming is

optimal

the same day that the devastating IPCC Report on 1.5 warming came out?

How else to read these

suggestions

(tweets embedded to the right) that the brutal reality of climate change

has finally arrived only now that it’s violently affected the United

States in the last two years?

The only dimension along which climate change has been “far off” was

in geography and political power. In 2013, even before Haiyan, 85% of

Filipinos reported personal experience with climate change impacts, 54%

of them describing them as “severe”

. In 2015,

54% of Hispanic

Americans

rated global warming as “extremely or very important to them

personally”. In 2017, monsoon-exacerbated floods affected 45 million in

South Asia

and

submerged two thirds of Bangladesh, including parts of the makeshift

hillside camps where nearly a million Rohingya refugees have been forced

to settle at risk of death by disease or

mudslides

.

When will developing countries or the

vulnerable

within developed

countries

get their say as frequently as do white op-ed

writers

or public

intellectuals

who command enormous platforms on seemingly any issue of their choosing

regardless of experience or expertise? They haven’t

yet.

Anti-alarmism and Western exceptionalism would have you discount the

value of those lives.

Other than harrowing research findings, I think a problem in climate communications is its failure to capture the imagination. A small chapter in the book poses a question I’ve wondered myself: Where is the great climate-change novel? Land war, nuclear winter, artificial intelligence, and other generation-defining threats have inspired influential works of art, but none springs immediately to mind about climate change.

“Mad Max: Fury Road”, while an action masterpiece, is only tenuously climate-related considering its desert dystopia was conceived before 1979. “Interstellar” was all right. I had been hoping from the trailer and its first half that “First Reformed” could be that movie, but I think it’s third act may have veered off message and it didn’t garner the Academy’s attention (not even an acting nomination for an outstanding entry by Ethan Hawke). Maybe “Woman At War” can be one.

Music-wise, I can only think of ANOHNI’s “4 Degrees” which was released in the context of the Paris Agreement. Thom Yorke, the vegetarian frontman of carbon-neutral Radiohead has said , “If I was going to write a protest song about climate change in 2015, it would be shit.”

Wallace-Wells offers some plausible explanations for its unique storytelling challenges, but I worry the answer may also be related to the aforementioned inequality.

Next on the climate reading list: Storming the Wall: Climate Change, Migration, and Homeland Security by Todd Miller

Federal disaster money favors the rich

An NPR investigation has found that across the country, white Americans and those with more wealth often receive more federal dollars after a disaster than do minorities and those with less wealth. Federal aid isn’t necessarily allocated to those who need it most; it’s allocated according to cost-benefit calculations meant to minimize taxpayer risk.

Put another way, after a disaster, rich people get richer and poor people get poorer. And federal disaster spending appears to exacerbate that wealth inequality.

The UK’s CO2 emissions fell for the sixth consecutive year

The longest run of reductions since the mid-19th century. Dr. Simon Evans points out this was driven entirely by reduction in coal demand, which comprise 7% of national emissions and is approaching zero in accordance with a 2025 timeline. Oil and gas-originated emissions have gone up.

Mann recently touched onthe recent article about the supercomputer simulation of climate-cloud formation feedback loops , which found global warming could soar by an additional eight degrees Celsius if a tipping point is breached. Mann cautions: “This effect only POTENTIALLY kicks in for CO2 levels of 1200+ ppm, much higher than we should EVER allow”