Late post because I lost an early draft from two weeks ago. I also initially had a bullet-point on David Wallace-Wells’ climate change book here but it morphed into its own post, posted just before this one.

Coverage of ’the migrant caravan’

Why wasn’t it covered this way from the beginning:

San Pedro Sula may not be well known, but from 2011 to 2014 it was the most violent city in the world. The only thing to do there is escape. The crime syndicates, which have complete control over the region and the power of life and death over its people, have in recent years plunged Honduras into an unofficial state of war…. President Trump talks about the migrant caravan as if it were an attempted invasion. In reality, Honduras and Central America have paid an enormous price precisely because of US policies.

This is what people are fleeing from, this landscape that seems to offer no future but killing or being killed. Despite their varied histories, the migrants all have in common the desire—or rather the need—to escape the violence of the drug gangs and the lack of work and opportunity in their country.

Jakelin Caal Maquin, age seven, was healthy when she left Raxruhá, Guatemala, with her father. On the evening of December 6, both were arrested, along with 161 other migrants, by the US border patrol in New Mexico, after illegally crossing the border. A few hours later, while in the custody of American border agents, Jakelin began suffering from a high fever and seizures; she was taken by helicopter to a hospital, where she died the next day from septic shock, dehydration, and liver failure. She had traveled two thousand miles, crossing the Mexican desert, enduring weeks of exhaustion and hardship to reach the US, because she knew that beyond its border she could hope for something better than the future her own country offered. She died in the very place she could have begun a new life.

Despite Trump’s many assertions, there is no evidence that criminals or drug traffickers formed any part of the caravan. The journalists who followed it have consistently reported that it is made up of ordinary, desperate people who are not criminals but are fleeing from criminals. Making these people seem dangerous, for example by claiming that the caravan has been infiltrated by “unknown Middle Easterners,” does, however, serve Trump’s interests, because it allows him to resort to emergency measures to keep the migrants from entering or remaining in the United States.

CBS also reported last week that 4,556 complaints over the past four years alleged unaccompanied migrant children were sexually abused in US custody

The New York Review article makes note of the diminishing numbers at refugee camps at the border and cite data from Mexican authorities: from a caravan originally estimated to be about 10,000 strong, 1,300 migrants returned home, 2,900 received humanitarian visas from Mexico and are living there legally, and 2,600 were arrested by US Border Patrol for attempting to cross illegally. The New York Times explored these migrants’ decisions to return to their home countries, attempt an illegal crossing, or settle in Mexico in the face of increasingly stringent policy under President Trump. It suggests that most of the asylum seekers who have given up on entering the United States were typically economic migrants who saw opportunity in joining the Honduran exodus:

Mexican officials said the data on people who have deferred or given up their quest for asylum in the United States reinforced an idea that is often raised by Mr. Trump: that many caravan members are not truly desperate for protection.

Immigrant advocates said that hype and false promises had attracted a group that was somewhat unrepresentative of typical asylum seekers. But they pointed to the roughly 4,000 members who had successfully entered the United States and had at least requested protected status to argue that most had legitimate claims.

Michelle Brané, the director of migrant rights and justice at the Women’s Refugee Commission, warned that while Mr. Trump’s tough policies may discourage the undeserving, they might also endanger people who need protection. She said they would likely drive vulnerable migrants into the arms of human traffickers, who promise to provide passage into the United States.

“It may look like it’s working in the short term,” Ms. Brané said, “But I don’t think it’s a long-term solution. It’s driving people further into the shadows and that’s exactly the opposite of what we want.”

It recalls this New Yorker article from last year summarizing an outstanding effort by 2016 MacArthur Fellow Prof. Sarah Stillman and her graduate journalism students at Columbia to make a record of migrants who were deported to their violent deaths “with the help of border agents, immigration judges, politicans, and US voters”:

Fear of retribution keeps most grieving families from speaking publicly. We contacted more than two hundred local legal-aid organizations, domestic-violence shelters, and immigrants’-rights groups nationwide, as well as migrant shelters, humanitarian operations, law offices, and mortuaries across Central America. We spoke to families of the deceased. And we gathered the stories of immigrants who had endured other harms—including kidnapping, extortion, and sexual assault—as a result of deportations under Obama and Trump.

As the database grew to include more than sixty cases, patterns emerged. Often, immigrants or their families had warned U.S. officials that they were in danger if sent back. Ana Lopez, the mother of a twenty-year-old gay asylum seeker named Nelson Avila-Lopez, wrote a letter to the U.S. government during Christmas week in 2011, two months after Immigration and Customs Enforcement accidentally deported him to Honduras. Nelson had fled the country at seventeen, after receiving gang threats. He’d entered the U.S. unauthorized and been ordered removed, but an immigration judge then granted him an emergency stay of his deportation so that he could reopen his case for asylum. An ICE agent told his family’s legal team that Nelson was deported because “someone screwed up,” and ICE alleges that the proper office had not been notified of the judge’s stay.

Francisco Cantú, the former Border Patrol guard whose article on border violence was previously linked to here, reviews a new book taking a historical look at the race-based violence and militarism of the American frontier and its modern incarnation in the southern Border Patrol. This is a history of atrocity—including “the lynching of thousands of men, women and children of Mexican descent from the mid-19th century until well into the 20th century”—that the Times this week reported is struggling to be preserved . The book is “The End of the Myth: From the Frontier to the Border Wall in the Mind of America” by the historian Greg Gandin:

Grandin’s chapters on the Border Patrol make evident the origins of many of today’s most egregious border-enforcement practices. When I read of the Mexicans who were routinely jeered at by federal agents in the 1920s as they crossed the bridge from Ciudad Juárez to El Paso, I thought of the agents who mocked a roomful of crying migrant children last summer after they had been separated from their parents. “Aqui tenemos una orquesta,” one agent joked—“We’ve got an orchestra here.” When I read of the workplace police raids that were conducted in the early nineteen-thirties, with the sanction of the Hoover Administration, as a “psychological gesture” to scare deportable migrants, I thought of the “show me your papers” law, passed in Arizona in 2010 and then adopted by other states, with the explicit hope of driving migrants toward self-deportation. When I read of the Border Patrol agents who admitted to reporters in the nineteen-seventies that, when pursuing migrant families, they would often try to apprehend the youngest member first, so that the rest would surrender in order to avoid being separated, I thought, inevitably, of the enactment last year of “zero tolerance,” which turned family separation into a national policy.

Because I served as a Border Patrol agent, from 2008 to 2012, Grandin’s account brought up more personal memories for me as well. Despite its white-supremacist roots, the Border Patrol has evolved into an agency where more than half of its members are of Latinx descent. Just as the military has long promised social mobility to immigrants and minority populations, the Border Patrol provides rare access to financial security and the privileges of full citizenship, especially for those living in rural border communities. In America, even at the individual level, citizenship politics often wins out over identity politics.

Sabrina, by Nick Drnaso

Our latest book club venture. Strong recommendation from The New Yorker and I thinkthe LA Review had the best take on it:

At its best, Drnaso’s work encourages readers—more thoroughly than might art with more explicit rendering of its characters—to recognize the interiority of other people. We pause, reflect, and introduce more of ourselves.

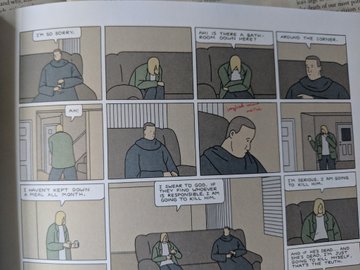

As someone unexperienced with graphic novels—I think I’ve only read Archie comics, “Watchmen”, and a few manga that were popular during high school—I was surprised by how well Drnaso accomplishes that expression of interiority through images drawn in the same style as airline emergency instructions (someone else’s comparison that I can’t seem to source at the moment). The illustrations leave a lot more implied that can text-based novels. Some choice examples with some short commentary:

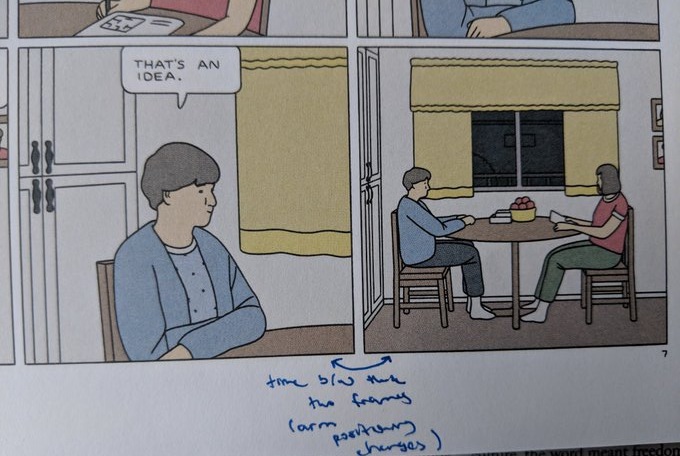

In these two frames, Drnaso can communicate a conversation hitting a lull without ever saying anything like “An awkward silence ensued.” Previous frames cut back-and-forth between the two characters as they took turns presenting their ideas so the zoomout brings both into frame emphasizing the physical presence of the silence. Sabrina’s (in blue) arm position has changed to denote the passage of time.

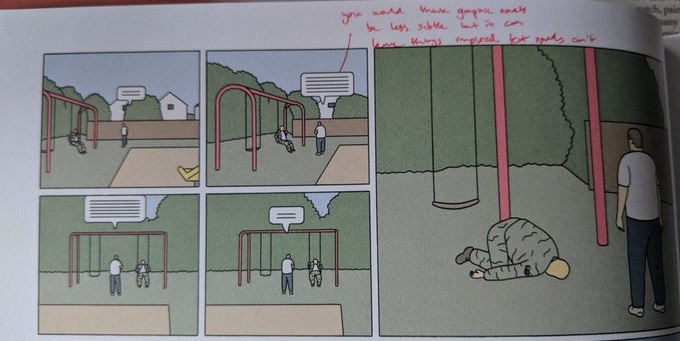

In context, we know exactly what Calvin is telling Teddy here; the exact grammar of how he phrases it is secondary to what the information means to Teddy. Teddy in shock collapses into an awkward, painful heap that would be difficult to describe in words.

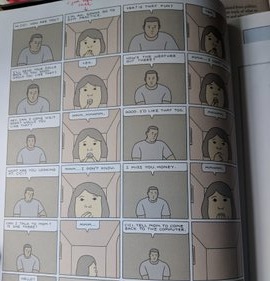

Exactly what it’s like to Facetime a child who’s too close to the camera. The conversation is over as soon as the child goes out of frame (both of the panel and of Calvin’s screen, which are the same perspective here).

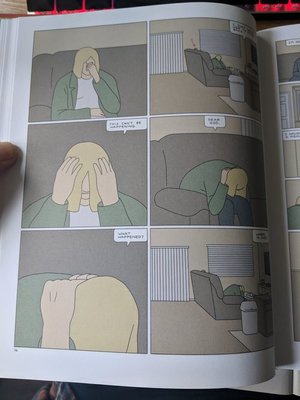

Teddy and Calvin are seated together. This page only uses angles emphasizing Teddy’s isolation, obscuring Teddy who’s seated right next to him…

…and the next shot is a comically contrasting cut to Calvin’s meager attempt to console him while wearing a Snuggie. The last three frames here communicate that Teddy has vomited without saying so or using an over-the-top onomatopoeic “BLEEECCCCHHHHH!!!” Just Calvin dipping his head slightly in second-hand embarrassment.

“I don’t know what it means to write a Marxist novel”

I guess the reason I feel skeptical of all that is it makes me feel that books have no potential to speak truth to power, they have no potential as political texts because of the role they play in the cultural economy… because of its position as a commodity.

Jason Hickel vs. Bill Gates/Steven Pinker/Max Roser on the declien of poverty

The finer points about data quality I don’t really care about (though on that, Branko Milanovic seems to be by far the most qualified ). I don’t find this graph being celebrated on Twitter particularly compelling. Poverty rates decreasing across all poverty lines over 25 years—especially these last 25 years—is a very low bar to clear and will be dominantly driven by China’s market reforms .

Lost in this level of aggregation is how many countries for which this invariance to poverty line does not hold (which I have no clue about but would like to see). And even in those cases, I’m not sure that’s a meaningful counterfactual upon which to evaluate the successes and inherent virtues of market fundamentalism.

“One of the strangest things an African scholar can do is move to Europe to study Africa.”

To commemorate completing my last economics class at Oxford:

“One of the strangest things an African scholar can do is move to Europe to study Africa.” @Nanjala1 in the preface to her book Digital Democracy, Analogue Politics: How the Internet Era is Transforming Kenya https://t.co/Jj8Qc0o28S pic.twitter.com/sP5Q4GU85d

— David Evans (@DaveEvansPhD) February 15, 2019