The IPCC report on climate change and land

In some ways, this is the most unavoidably political document that the IPCC has ever published. Its report last year, on the dangers of global warming beyond 1.5 degrees Celsius, called for an unprecedented transformation in the globe’s energy system… But talking about the energy system is, in this context, relatively easy… land is different. It is home, and the possibility of home. The relationship between people and land is the most treasured and unresolved idea in global politics.

The biggest of these issues: Land can’t really multitask.

“Land can’t, at the same time, feed people, and grow trees to be burned for bioenergy, and store carbon,” Stabinsky said. “That conflict of what’s going to take priority as we face greater and greater climate challenges” defined the talks, she said. “There’s going to be more and more desire to try to use land to pull carbon out of the atmosphere, and that’s going to interfere with food production.”

To address climate change, we will need to reduce our use of fossil fuels, and replace energy generated in the past (by long-dead plants) with energy generated today (by wind turbines, solar panels, and uranium atoms). But, this report adds: We must do all that in a house of only 52 million rooms, the majority of which already serve as someone’s bedroom, bathroom, or kitchen. And those 52 million rooms must stage not only the unending drama of the human family, but also—as far as we know—every other living thing in the universe.

How are you even supposed to talk about that?

The remarkable efficiency of the kidnapping industry

One of the most interesting things I’ve read this year. If I were designing an undergrad or high-school economics syllabus, I’d make it an assigned reading. Market formation, price discrimination, luxury goods, insurance dynamics, information asymmetry, signaling, game theory, and more all in a real high-stakes setting and very well-written. So much is great, but a small sample:

“Kidnappers make rational choices,” Shortland writes. Like the professionals on the other side, kidnappers perform research, assess risks, manage costs, and, if they’re in it for the long term, build reputations for orderly resolution. Some groups even develop an infrastructure to support their operations, though this is expensive and may increase the number of expectant beneficiaries (if operations are mounted on credit, for example).

When kidnappers keep hostages for days, weeks, or months, most invest in keeping them alive (a corpse is not worth much, except in the Iliad) and in decent health. Captives with medical conditions are usually allowed to receive medications; in 2010 al-Qaeda let a French woman with breast cancer take chemo drugs. Somali pirates are governed by a strict code of conduct that fines guards for hurting hostages; there’s even a printed “Pirate’s Handbook.” They have been known to send their counterparties receipts for items, such as bottled water, procured for the proper maintenance of the captives. Criminal groups want to be seen as trustworthy adversaries bargaining in good faith—if the ransom is paid, the hostage is released—and know that killing or harming hostages will imperil negotiations and, in some cases, lead to armed intervention.

The UN forbids the transfer of money to designated terrorist groups; the US Treasury, the EU, and other governmental bodies also maintain such lists. Private persons and entities cannot legally make concessions to proscribed groups, and if they do, their insurers cannot legally reimburse them, though ransom-payers are rarely if ever prosecuted.

“If it’s criminal, it’s legal,” a British bureaucrat told Shortland of ransom payments. But it’s not always clear which category kidnappers fit into. Some terrorists pretend to be part of criminal organizations so that they can legally collect ransoms. Shortland reports that when a Somali told British negotiators that he represented the “commercial arm” of al-Shabaab, the jihadist fundamentalist group, “they had to explain that this was not sufficiently removed from the parent organization to have a payment authorized.”

Current Affairs on Steven Pinker

I guess I largely agree with this takedow and the bullet-pointed quotes are damning. His endorsement of Quillette this week has predictably alreadyaged poorly . From my perspective, things improving over time is a pretty low bar to clear; new optimists seem to argue that the fact that most people are ignorant of this general trend is evidence that the status quo is justified. I don’t understand that reasoning and it’s weird how pervasive that idea is.

That said, I’ve said before that I don’t think either side of the Pinker-Hickel spat are the best representatives of their perspectives. I also wish Nathan Robinson’s tone weren’t itself frequently grating; this is a lot of work and some good argumentation to squander packaging in immature language. I haven’t found a publication that self-identifies as leftist that is consistently readable (e.g. Jacobin, Current Affairs).

The development of accurate short-term weather forecasting

The weather apps we often mistake as representing the frontier in meteorology are usually idiosyncratic prediction models based on a more aggregated global model of which the complexity and miraculous accuracy boggles the mind:

Landing a spacecraft on Mars requires dealing with hundreds of mathematical variables. Making a global atmospheric model requires hundreds of thousands.

The article begins with two compelling wartime applications of accurate weather forecasting. The first is an argument that superior meteorologists determined the Allied victory on the Western Front. The second is of a Nazi espionage mission:

In the Northern Hemisphere, storms tend to move from west to east, so any prediction of what lay in store for Europe relied on knowing what was happening in the Atlantic. The Allies, who were in control of all the major landmasses that lined the ocean, had the upper hand. The Nazis had to use long-range aircraft and secret weather ships to gather observations. The Allies tried to sink those ships, but the Nazis also made use of radio reports of cancelled English soccer matches for hints about weather to the north.

So, as Blum explains, in 1942 the German government came up with an ingenious solution. With help from the Siemens-Schuckertwerke group (a predecessor of the modern-day Siemens) and others, it developed a series of automated weather stations: these were an intricate array of pressure, temperature, and humidity sensors, encased in storm-resistant metal containers and equipped with batteries and a radio antenna. Some would hitch rides with the Luftwaffe and transmit weather readings from remote locations on the edge of Europe. By 1943, the devices were powerful enough to communicate across the Atlantic. That year, a Nazi submarine sneaked to the northernmost tip of Newfoundland, where a team of German soldiers took ten cannisters ashore on two rubber dinghies. For the plan to work, the weather station needed to stay undetected after it had been left in the wilderness, so they labelled the equipment “Canadian Meteor Service” and scattered the site with a host of American cigarette packs. Only in 1981 was the ruse discovered.

Two field trials successfully suppressed procreation in invasive tiger mosquitoes

When male Ae. albopictus from the HC population mated with females with the native double infection, all the resulting embryos died, as would be predicted because the females were not infected with the wPip strain that infected the males (Fig. 1a). However, such embryo lethality did not occur when wPip-infected males mated with females that were also infected with the wPip strain (Fig. 1b). Thus, a risk in the authors’ approach was that, if any wPip-infected females were released along with males, they would spread the wPip infection rapidly through the wild population, eliminating the population-suppressing effects of the wPip-infected males.

Zheng and co-workers’ major innovation was their method of preparing HC mosquitoes for release. In facilities that mass-rear mosquitoes, male pupae are usually mechanically separated from female pupae on the basis of size differences. Using this procedure to prepare groups of male mosquitoes led to a female contamination rate of approximately 0.2–0.5%, necessitating a secondary, manual screening to remove female pupae, recognized by their distinctive anatomy. However, this labour-intensive manual screen substantially limited the total number of mosquitoes that could be prepared. Zheng et al. eliminated the need for the manual screen by subjecting the HC pupae to low-dose radiation that sterilized females but that only slightly impaired male mating success. As a result of eliminating the manual screen, they were able to increase the number of male mosquitoes that could be released by more than tenfold.

Population-suppression strategies crucially depend on the ratio of released males to wild males. Thus, Zheng et al. used mathematical modelling and cage experiments to calculate the optimal sizes and timings of mosquito releases. During the peak breeding season, the rearing facility produced more than 5 million male mosquitoes per week, leading to the release of more than 160,000 mosquitoes per hectare per week at the test sites. Zheng et al. monitored the numbers and viability of eggs produced by wild mosquitoes, as well as the abundance of adult mosquitoes and the rates at which they bit humans at test sites and at nearby control sites (where no HC males had been released).

It sounded so much simpler in my head: inject mosquitoes with science, release them to the wild, save lives.

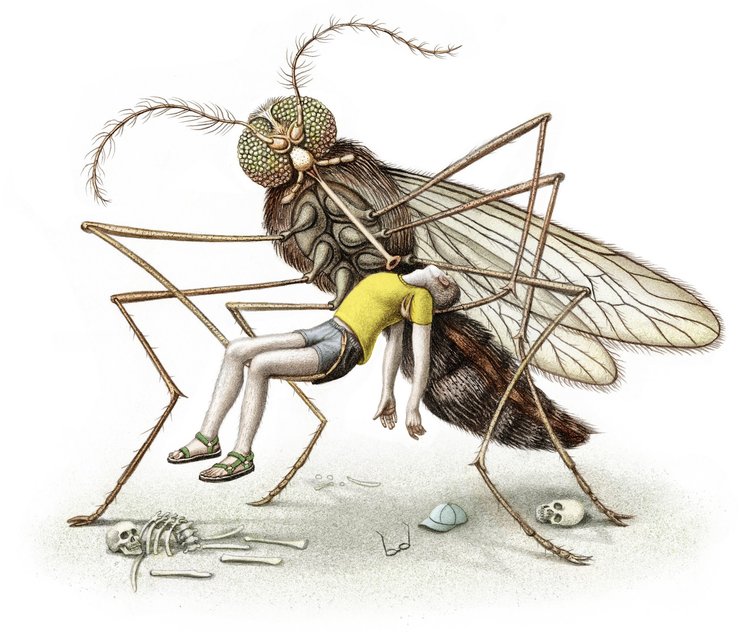

Coincidentally timed (I assume since it makes no reference to the study) was a NYT opinion piece on the primacy of mosquitoes , featuring the nightmare-fuel illustration below:

Mosquitoes may have killed nearly half of the 108 billion humans who have ever lived across our 200,000-year or more existence.

That’s the premise of the author’s new book, from which the article is adapted. As is often the case, I don’t know what makes this an “opinion” article.

The discourse machine

I read this months ago and forgot about it before I could link it here. Fortunately some particularly terrible groupwork this week by the New York Times’ headline writer, opinions section, and editor in chief conspired to remind me.

The essay creatively alternates between the perspectives of an editor, writer, and reader and culminates in an argument against the institution of the newspaper op-ed. It reads quite performatively and explicitly points a finger at the practice of excerpting so I’ll indulge it this time and just urge you to read it.