Easiest bits first. There is so much of value in this book. In

particular, Manne’s multi-layered formulation of misogyny not as simple

“hatred of women” but as a self-perpetuating system of behavior policing

is convincingly argued and I think should be taught widely. By this, I

mean beyond philosophy including fields such as my own in economics,

which has proved notoriously incapable of incorporating such systemic

phenomena in its analytical frameworks. It is important.

The book is unfortunately very difficult to read. It is an academic book

that the reader will quickly learn is not oriented towards general

audiences. Even as an academic in a field of bad writers and opaque

equations, this was frequently impenetrable and as a result, I took a

break from continuing the book for about seven months. Lots of Goodreads

reviews have voiced this frustration but I particularly relate to one

that singled out the following sentence from page 180:

The implicit modus ponens here is too seldom tollensed.

I involuntarily said, “Oh fuck off” within earshot of a children’s

playground when parsing that sentence before highlighting it and noting

“wtf” next to it. As someone who went to college intending to major in

philosophy, I get the temptation of verbosity but an editor should have

axed that on sight. The concepts aren’t even that difficult to express

in simple writing and frankly, it is a wasted opportunity to invite

marginalized voices to participate in philosophy, a field that like mine

suffers from elitism and a lack of diversity.

Beyond this, it is a bit disorganized; the chapters could be better

distinguished and there are too many large footnotes throughout. The

constant forward and backward references to previous and forthcoming

chapters (e.g. “We will see in Chapter 5 how this manifests...”,

“recall in Chapter 2 how…”) breaks the flow of an already laborious

read.

The writing isn’t bad. The examples provided, drawn from news stories,

literature, movies, and other art, are well chosen. Manne’s writing is

very quotable and there are a lot of segments where as a reader you just

think, “I’m familiar with this concept but just hadn’t seen it

systematically put into words before.” Case in point, a lot of people

engaged enthusiastically with this tweet of

mine

, which was

a literally random sentence from the book (replies seem to be hidden for

some reason). I like in particular the exposition of exonerating

narratives. I’d recommend this review of the

book

—it’s

what got me to buy it in the first place.

Now, the bad parts and they are indeed very bad. In particular, this

book is deeply irresponsible in its discussions of race and empire.

Manne to her credit begins with a positionality statement acknowledging

her limited vantage point and throughout makes reference to misogynoir

and the privileged status of white women like herself. Nonetheless, the

racial analysis is severely lacking and oftentimes harmfully so,

disappointing in a book that bills itself as intersectional.

The first major stumbling block I identified is from her chapter on

victim-blaming, namely the public’s predisposition to not believe the

accounts of victims of misogyny. In it, she considers reasons that would

bring women to make public their grievances in anticipation of

too-common and nonsensical counterarguments that the victim would

somehow benefit from the attention. As the Me Too movement has made

undeniable, this he said/she said battle unfortunately places an unfair

burden of proof on the alleger, who is often a stranger to the public

sphere lacking the resources and benefit of familiarity of their more

powerful, typically male abusers. Manne is convincing in making the

point that if it were the case that the accuser seeks to attract

sympathy, this is a terrible way to do it: the public is primed to

preserve its goodwill towards the familiar and powerful and is prone to

intrusively scrutinizing imperfect victims. The burden of proof is

unbelievably daunting, often humiliating, and evidence is routinely

purposely destroyed. Clearly, no sane person would willingly go through

this ordeal without at least the truth on their side.

Then Manne off-hand (page 238) says that “given... the paucity of

analogues running in the other direction, gender-wise”—meaning given

that we rarely see actual evidence of malevolent accusers—we can

dismiss this motive. This was shocking to read a few days after a

national commemoration of Emmett Till’s 79th birthday and during a

moment where video footage keeps surfacing of white women using their

privileged status in attempts to weaponize white supremacy through some

wrongly perceived or outright invented abuse, i.e. “Karens”, to use the

ironically now-gentrified nomenclature. Of course, the most high-profile

recent example is that of Amy Cooper calling the police on Christian

Cooper in Central Park. You’ll also remember this immediately

recognizable dynamic gives the movie “Get Out” its climax when a police

car finds Daniel Kaluuya’s character strangling Allison Williams'

without context. “Who are they gonna believe?” is indeed a weapon and it

is unfair to dismiss that it is wielded by the powerful, who are

sometimes women. Manne’s analysis, in my understanding, cannot

accommodate this complication, wherein in white women have repeatedly

been shown to abuse their credibility as victims to threaten the lives

of innocent others. We lament how the Black Lives Matter movement has

been so dependent on fortuitous camera footage to inspire the support of

non-Black people because they face the same unjust burden of proof.

Believe survivors, of course, but where there is intersectional power,

there is complexity beyond what Manne’s framework permits.

Chapter 8 is mostly a reflection on Hillary Clinton’s election loss to

Donald Trump. Like other Goodreads reviewers here, I had followed Manne

on Twitter for a while before getting to this chapter and it is clear

and understandable that she identifies personally with the undeniably

sexist treatment Clinton has received throughout her very public

career.

Unfortunately, the relatability of an objectively qualified and

competent white woman occupying elite space has clearly clouded her

judgment to the point of being unable to consider Clinton’s objective

flaws. Chapters earlier, Manne makes the vital point that we cannot hold

victims of misogyny to the impossible standard of being perfect victims.

In fact, she invokes Michael Brown to make this point. Why then does

Manne do Clinton the disservice of making her out as a perfect

politician? Decades as arguably the most powerful woman in the world

straddling neoliberal economics, a racist and punitive war on crime, and

a hawkish war agenda, but Manne will only concede that some unspecified

policies were “misguided” without elaboration. When she later

considers Clinton’s support of the Iraq War (which she introduces as

Bernie Sanders’ “controversial remarks about Clinton’s being

unqualified”), she does so only to point out that “Donald Trump’s vice

president, Mike Pence, also voted for the war in Iraq” and that he

received less scrutiny.

Manne also uses this chapter to vaguely highlight the plight of Alice

Goffman, completely omitting the racial-exploitative nature of the

controversy surrounding her. There is probably a sexist component to her

treatment—I was a b-school undergrad not remotely interested in

academia at the time so cannot speak to what the backlash was like—but

the absence of context is odd given Manne’s tendency elsewhere to

elaborate on the context behind all her case studies and how they fit

the discussion at-hand. It is also telling that Manne’s next book

reportedly will include a chapter on Elizabeth Warren’s run in the 2020

Democratic primary. Manne on Twitter has repeatedly and explicitly

rejected the notion that there could be a non-gendered reason for

favoring any candidate besides Warren. I don’t think I need to appeal to

support of Clinton over Sanders in 2016 and initially Warren over

everyone this cycle (before strongly favoring Sanders) to call this

ridiculously out of touch and reflective of an elitist tunnel vision.

This limited perspective palpable throughout the book contributed to my

hesitation to finish. Even if we were to accept the premise, there is no

good reason to repeatedly narrow your scope of analysis to white, rich,

powerful politicians whose chief downfall is that they’ve only occupied

the second most powerful political positions in the United States. Julia

Gibbard hardly constitutes diversification. There is a wealth of

material ripe for philosophical analysis outside of the white

Anglosphere.

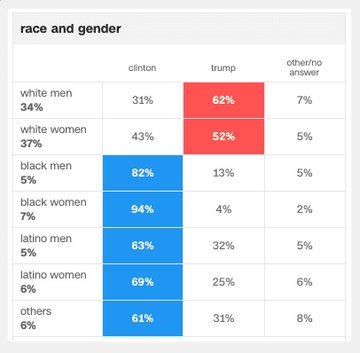

Finally, there is the matter of Manne’s analysis of the 2016 election. You would not know it from her treatment, but 82% of Black men, 63% of Latino men, and 61% of non-white others voted for Clinton. Sure, these are lower than the 94% and 69% of their female counterparts, but Manne’s analysis is so unable to consider non-white agency that one gets the sense that these facts are mere inconveniences. The racial dimensions of the election of a billionaire who popularized the Birther movement, ran on a platform explicitly equating Mexicans with rapists, and who labeled Africa a collection of shithole countries are completely absent from Manne’s election autopsy.

This isn’t to say she does not talk about race in the chapter:

My sense is that people in liberal and progressive circles were not generally as proud to vote for Clinton as President Obama, despite their very similar policies and politics, and the fact that each was or would have been (respectively) a history-making president

Beyond this casual equation of breaking the highest gender and racial barriers, how deeply must one lose themselves in the professor bubble that they cannot fathom a non-gendered reason that an upstart Obama would have an appeal that Clinton did not? It is completely lost on Manne that, as the numbers above attest, the reason the United States does not currently have a female president is because of racism. Is it possible that white women may be active participants and benefactors in the perpetuation of white supremacy (I’m thinking, for example, of the legacy of female participation in slave ownership as documented by the historian Stephanie Jones-Rogers)? In Manne’s shockingly aracial analysis of why white women voted for Trump, it does not seem so:

It turns out that women penalize highly successful women just as much as men do... In the days following the election, it was common for those of us grieving the result to judge the white women who voted for Donald Trump even more harshly than their white male counterparts. I was guilty of this myself. But... I subsequently came to redirect a good portion of my anger toward the patriarchal system that makes even young women believe that they are unlikely to succeed in high-powered, male-dominated roles.

How can one square this takeaway with the voting patterns of non-white women unless “women” here implicitly means “white women”? Does Manne suggest non-white women think themselves more likely to succeed in high-powered, male-dominated roles? She refuses to entertain the notion of white female racism:

…almost no black women and relatively few Latina women voted for Trump over Clinton. Is racial difference part of what makes for psychological self-differentiation from Clinton? Or was the obvious fact that these women had more to lose in having a white supremacist-friendly president rather an overriding factor in blocking the underlying dispositions that might otherwise have been operative?... Whatever the case, it seems plausible that white women had additional psychological and social incentives to support Trump and forgive him his misogyny... As white women, we are habitually loyal to powerful white men in our vicinity.

By this account, white women are not racist. No, they are just more embedded in white culture and thus have a proclivity to forgive while Black and Latina women are just looking out for what they have to lose. As for non-white men’s overwhelming support for Clinton, it doesn’t get mention at all.

I realize the bulk of this review is negative—it’s turned out much

longer than I intended—and hones in on one chapter of nine. These

missteps were particularly egregious to me maybe because they spoil what

is otherwise such a valuable offering. I would quite readily recommend

the first seven chapters to anyone with an open mind about dense

writing.

As an aside, this book was my first time reading an excerpt from

then-anonymous Chanel Miller’s impact statement in the Brock Turner

case. It’s a timeless piece of writing.