By necessity, my work draws from interdisciplinary approaches and collaborations across the social and natural sciences. I also maintain a secondary interest in historical political economy as it pertains to the determination and persistence of social inequalities and deprivations.

Working papers

Global income distributions and social welfare under climate change

- Revision in progress, 2025 draft available upon request

- JMP version previously circulated with the title “Climate inequality”

Understanding how climate change impacts global economic inequality is critical to the design of equitable and politically viable climate policy. Yet where evidence of this relationship is available, analysis is generally limited to coarse comparisons of country-level aggregates, remaining agnostic to disparities across individuals within those countries. This paper advances this literature using newly available distributional income data to incorporate within-country dimensions of this ‘climate inequality’. First, I document new evidence that temperature shocks persistently exacerbate inequalities within countries by disproportionately reducing income growth among the lowest income-earners, especially in warm-climate economies. Second, I use these empirical results to compare the historically observed distribution of global income to its counterfactual distribution had global warming been stabilized at 1980 levels. I estimate that systematic warming between 1980-2016 increased global income inequality by 4.0% [1.6,6.6], with absolute increases in between-country and within-country inequality contributing equally to this total effect. These contributions in turn correspond to proportional increases in inequality of 2.6% [0.0, 5.6] within countries and 8.7% [4.9, 13.3] between countries. To my knowledge, these distributional results constitute a novel contribution to the climate impacts literature and altogether offer the most comprehensive evidence yet of the globally regressive economic impact of climate change.

Temperature, institutions, and the political climate

- Revision in progress, 2025 draft available upon request

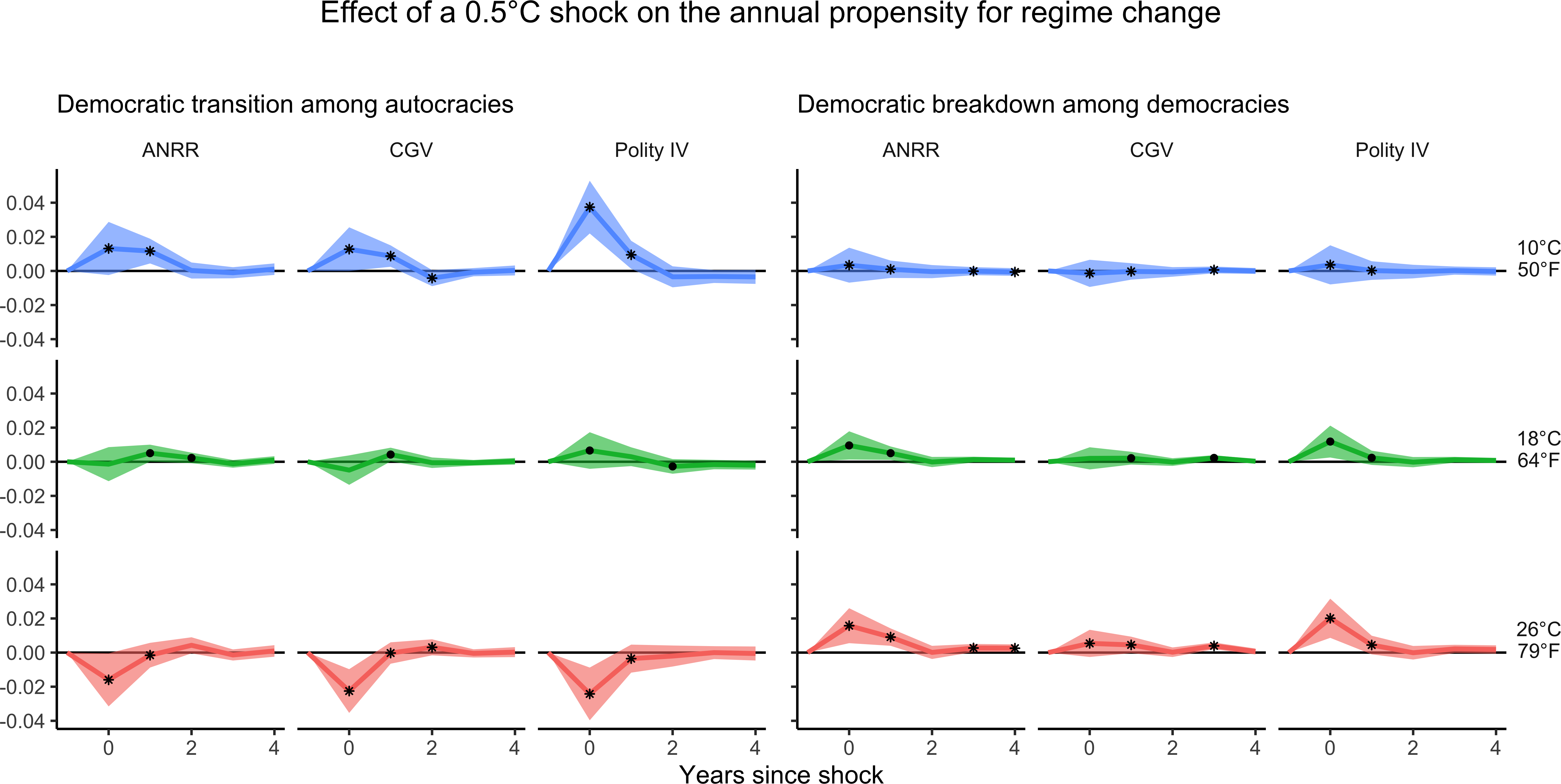

Despite widespread recognition of climate change as a threat to global stability, its political consequences remain undertheorized. This paper derives two competing hypotheses of how political preferences and institutions respond to environmental shocks by repurposing influential theories of demand-led political transition. The “mercury uprising” hypothesis posits that adverse climate shocks reduce the opportunity cost of contesting autocratic rule, thereby increasing pressure for democratic reform. In contrast, the `state of exception’ hypothesis views these shocks as crisis events that prompt citizens to trade off negative liberties for perceived security, diminishing support for democracy and manifesting in autocratic drift. I test these hypotheses by estimating the dynamic impacts of identified temperature shocks on survey-based proxies for democratic demand and on institutional quality, using multi-valued and binary measures of democracy. Results indicate that economically adverse shocks reduce democratic sentiment and increase the risk of democratic backsliding. A 0.5$^\circ$C shock reduces the annual probability of democratization in autocracies by 1.5–3.7 percentage points, depending on local climate and the democracy measure used. In warm-climate democracies, the same shock increases the risk of democratic reversal by 0.6–2.0pp, with no comparable effect in cooler, typically more developed contexts. These findings support the state of exception hypothesis and suggest that sufficient state capacity may insulate democracies from climate-driven political disruption.

Work in progress

Evidence of a drought effect on the hazard into spousal violence

with Tanushree Goyal

A write-up is available upon request. Results reported here are preliminary.

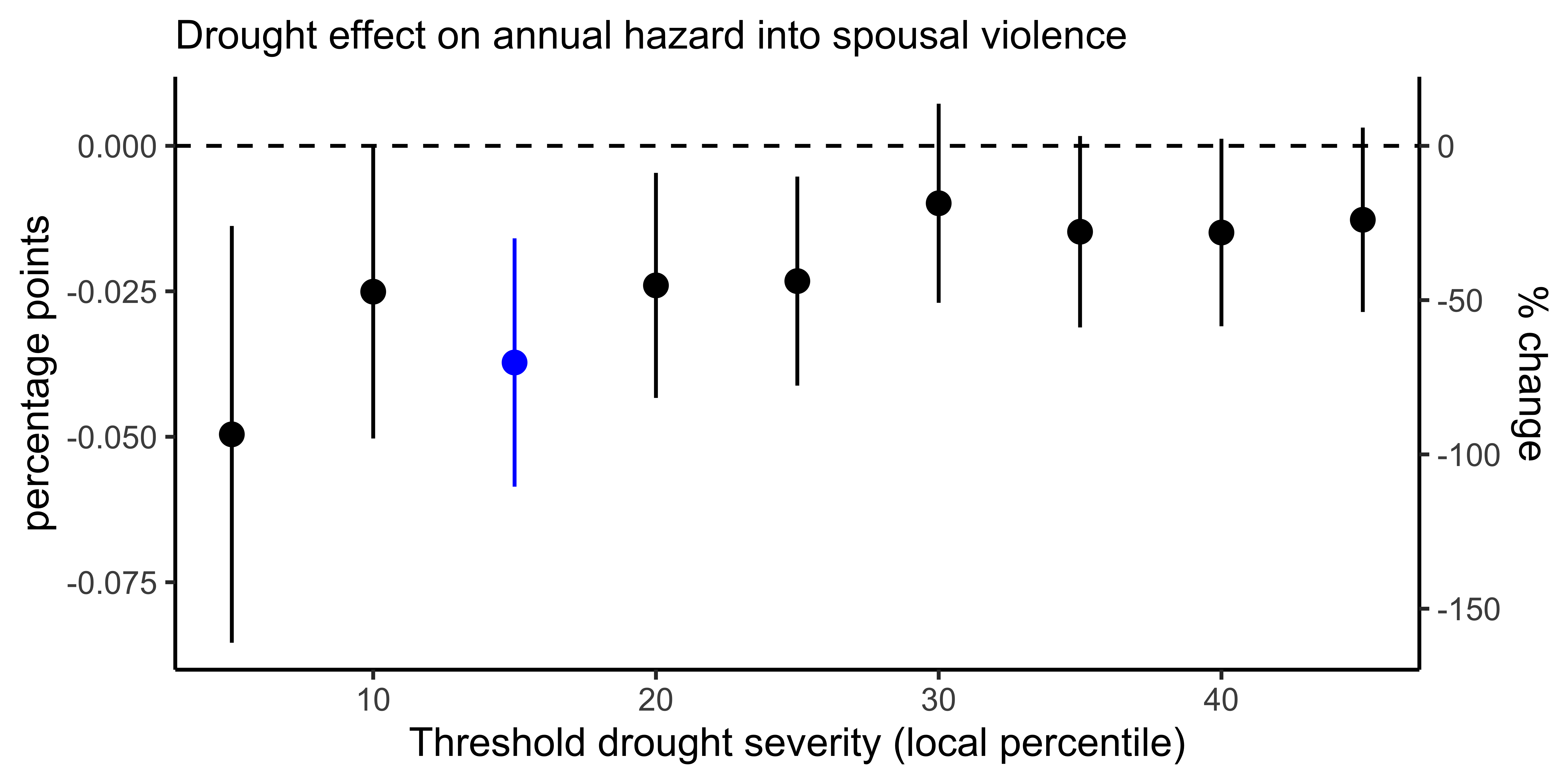

This project investigates how droughts influence the onset of intimate-partner violence. We combine high-resolution precipitation data with duration data derived from household domestic violence surveys in India to estimate how negative income shocks impact the risk of marital violence. We find that a negative precipitation shock of a magnitude expected once every 4–5 years \textit{decreases} the probability of first-time spousal violence by 0.037 percentage points in the formative years of marriage, representing a 70% reduction from the unconditional baseline hazard. As a complementary analysis, we revisit a recent study linking similar drought shocks to child marriage, applying updated methods and improved data. We now find that droughts reduce the hazard into early marriage both in Indian contexts practicing dowry payments and in Sub-Saharan African settings with bride-price customs. These effects are also largest for marriages occurring later in life. Our findings suggest a much more consistent relationship between drought and the timing of marriage across cultural contexts and that child marriage is likely more culturally coerced than economically motivated.

Publications

Large potential reduction in economic damages under UN mitigation targets

Marshall Burke, W. Matthew Alampay Davis, and Noah S. Diffenbaugh (2018)Nature 557(7706): 549–553.

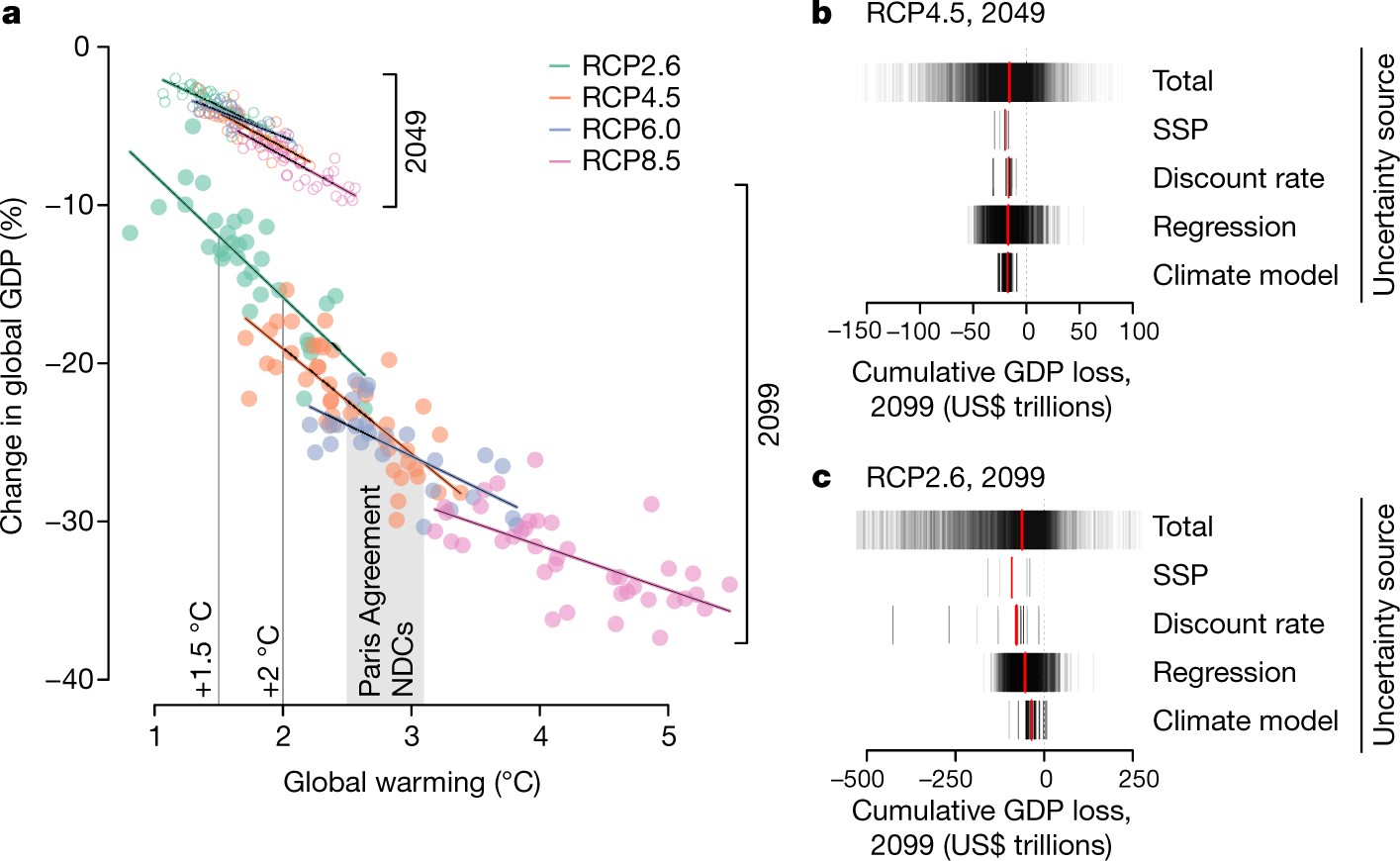

We present a probabilistic framework for assessing aggregate economic impacts of anthropogenic warming. Our construction decomposes uncertainty associated with mid-century and end-of-century economic projections into distinct sources of uncertainty associated with i) econometric estimation of the economic effects of environmental change, ii) climate models of the spatial distribution of anthropogenic warming, iii) the projected schedule of greenhouse gas concentrations associated with a radiative forcing, and iv) the social discounting regime of choice. We apply this framework to characterize the economic benefits of climate policy, emphasizing how achieving the most ambitious mitigation targets of the 2015 Paris Agreement would obviate essentially certain economic calamity that will otherwise concentrate in developing countries.

Paper materials and links

- Paper: official $\cdot$ ungated

- Replication files

- Stanford ECHO Lab website

Select citations

New York Times $\cdot$ The Guardian $\cdot$ Governors of New York, California, and Washington $\cdot$ IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C (SR15) $\cdot$ MSNBC (TV) $\cdot$ “The Uninhabitable Earth” by David Wallace-Wells $\cdot$ Rezo $\cdot$ Bernie Sanders $\cdot$ US House Committee on Financial Services $\cdot$ IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR6-WGII)

Select press

Nature $\cdot$ Stanford $\cdot$ Bloomberg $\cdot$ CBS (TV) $\cdot$ The Guardian $\cdot$ Reuters $\cdot$ The Hill $\cdot$ Yahoo $\cdot$ Axios $\cdot$ The New Yorker $\cdot$ Business Insider $\cdot$ Rolling Stone $\cdot$ The Daily Show (TV)

Combining satellite imagery and machine learning to predict poverty

Neal Jean, Marshall Burke, Michael Xie, W. Matthew Alampay Davis, David B. Lobell, and Stefano Ermon (2016)Science 353: 790–794.

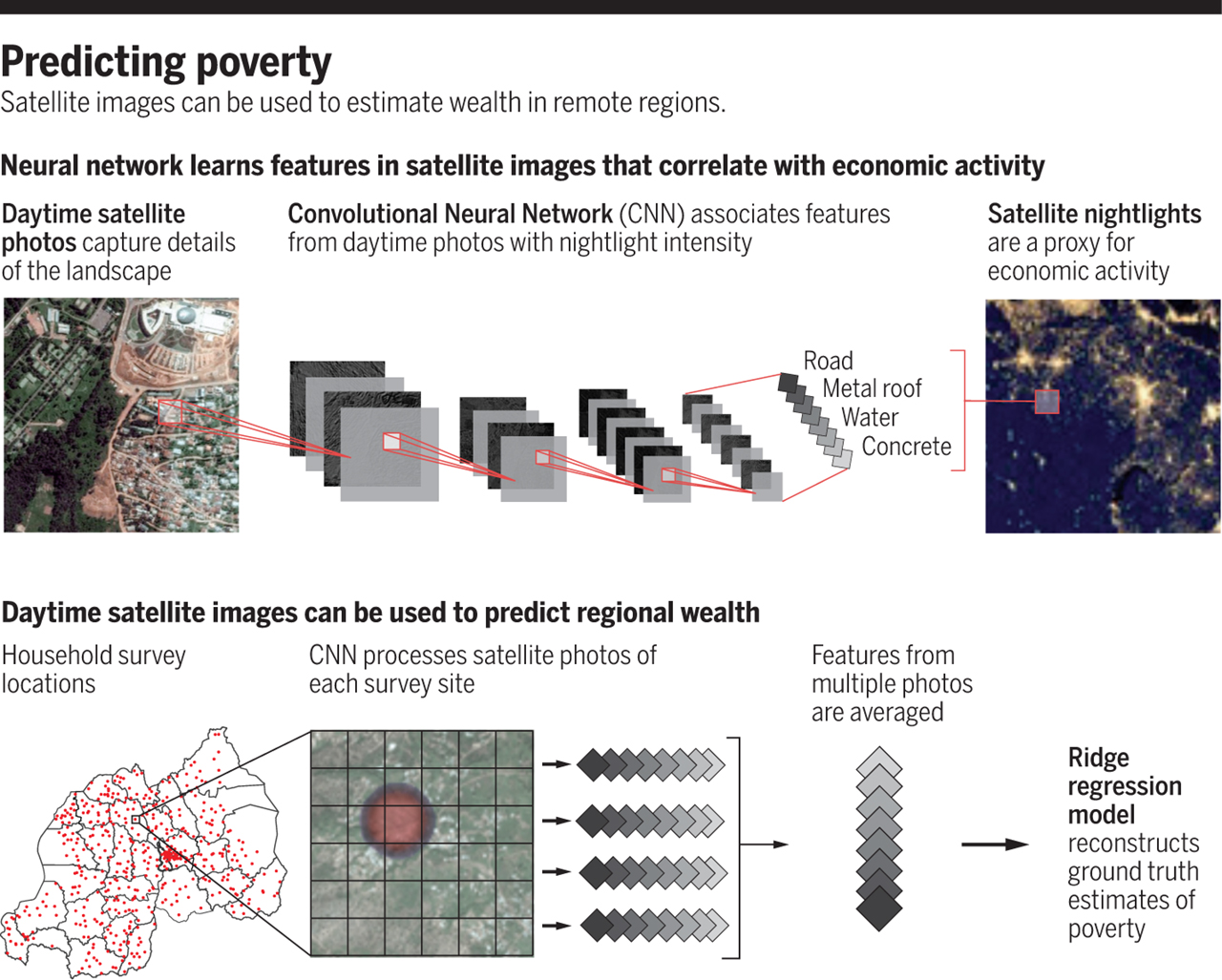

Efforts to study and design policy addressing the challenges of global poverty and inequality are hampered by the infrequency and prohibitive expense of reliable measurement of welfare, particularly in the developing world. Here we demonstrate a scalable method for overcoming this data scarcity which works by extracting economic information from an unconventional but inexpensive source of data with increasingly frequent and essentially global coverage: high-resolution daytime satellite imagery.

Our “transfer learning” pipeline proceeds by first assigning a convolutional neural network model pre-trained for generic image classification the task of identifying features in the daytime imagery predictive of night-time luminosity, a crude proxy for economic activity. In effect, the CNN learns to produce a nonlinear mapping from the unstructured images to a low-dimensional vector representation of its most economically informative features. Ridge regression models are then optimized to produce out-of-sample estimates of consumption expenditures and asset wealth. In an initial application to five diverse sub-Saharan African countries—Nigeria, Tanzania, Uganda, Malawi, and Rwanda—our entirely open-source models are able to explain up to 75% of the variation in village-level outcomes as measured by household surveys, demonstrating potential to reduce misallocation costs in the administration of targeted social programs.

Paper materials and links

- Paper: official $\cdot$ ungated

- Replication files: code and data $\cdot$ closed issues

- Authors’ blog posts: summary $\cdot$ genesis $\cdot$ update

- Sustain Lab website

- Non-technical animated video summary

Select press

Science $\cdot$ Stanford $\cdot$ The Washington Post $\cdot$ BBC $\cdot$ Scientific American $\cdot$ The Atlantic $\cdot$ The Onion $\cdot$ Bill Gates $\cdot$ Center for Global Development